Cardiff and Caerphilly... Ancient Welsh Castles

The characteristic types of castles in the

twelfth century were the rectangular keep

and the shell keep; in the thirteenth the

concentric castle. The square

keep seems most characteristic of

Norman military architecture; the Tower

of London, Rochester, Newcastle, Castle

Rising, are well-known examples, and there

are many more in a good state of preservation;

there are many more solid square

keeps than shell keeps well preserved, but

this is simply due to the greater solidity

of the former; the shell keeps were far

more numerous in the twelfth century;

and the reasons for this are obvious—the

rectangular keep was much more expensive

to build, and it was too heavy to erect on the artificial mounds on which the Norman

architects generally founded their castles.

The keep of Cardiff Castle is one of the

most perfect shell keeps in existence. It

is built on a round artificial mound, surrounded

by a wide and deep moat—the

mound and moat being, of course, complements

of each other. Such mounds and

moats are common in all parts of England,

and in Normandy. They are not Roman,

nor British, nor are they, as Mr. G. T.

Clark maintained, characteristic of Anglo-Saxon

work. They are essentially Norman,

and a good representation of the

making of such a mound may be seen in

the Bayeux Tapestry, under the heading—‘He

orders them to dig a castle.’ When

was the Cardiff mound made? Perhaps

the short entry in the Brut gives the

answer: “1080, the building of Cardiff

began.” It would then be surrounded by

wooden palisades, and surmounted by a

timber structure, as a newly made mound

would not stand the masonry.

The shell

keep was probably built by Robert of

Gloucester, and it was probably in the

gate-house of this keep, that Robert of

Normandy was imprisoned. A shell keep

was a ring wall eight or ten feet thick,

about thirty feet high, not covered in, and

enclosing an open courtyard, round which

were placed the buildings—light structures,

often wooden sheds, abutting on the ring

wall—such as one may see now in the

courtyard of Castell Coch. The shell keep

was the centre of Robert’s castle, but not

the whole. From this time dated the

great outer walls on the south and west—walls

forty feet high and ten feet thick

and solid throughout. The north and

east and part of the south sides of the castle

precincts are enclosed by banks of earth,

beneath which, the walls of a Roman camp

have recently been discovered. These

banks were capped by a slight embattled

wall. Outside along the north, south and

east fronts was a moat, formerly fed

by the Taff through the Mill leat stream

which ran along the west front. The

present lodgings, or habitable part of the

castle built on either side of the great west

wall, date mostly from the fifteenth century.

The earlier lodgings were, perhaps, on the

same site—though only inside the wall; a

great lord did not as a rule live in the

keep, except in times of danger.

The area of the enclosure is about ten

acres—more suited to a Roman garrison

than to a lord marcher of the twelfth

century. That the castle was difficult to

guard is shown by the success of Ivor

Bach’s bold dash,

c. 1153-1158. Ivor ap

Meyric was Lord of Senghenydd, holding

it of William of Gloucester, the Lord of

Glamorgan, and, perhaps, had his headquarters

in the fortress above the present

Castell Coch. “He was,” says Giraldus

Cambrensis, “after the manner of the

Welsh, owner of a tract of mountain land,

of which the earl was trying to deprive

him. At that time the Castle of Cardiff

was surrounded with high walls, guarded

by 120 men at arms, a numerous body

of archers and a strong watch. Yet in

defiance of all this, Ivor, in the dead of

night secretly scaled the walls, seized the

earl and countess and their only son, and

carried them off to the woods; and did not

release them till he had recovered all that

had been unjustly taken from him,” and a

goodly ransom in addition. Perhaps the

most permanent result of this episode was

the building of a wall 30 feet high between

the keep and the Black Tower—dividing

the castle enclosure into two parts and

forming an inner or middle ward of less

extent, and less liable to danger from such

sudden raids.

Cardiff Castle was much more than a

place of defense; it was the seat of

government. The bailiff of the Castle

was

ex officio mayor of the town in the

Middle Ages. The Castle was also the

head and centre of the Lordship of

Glamorgan. This was divided into two

parts—the shire fee or body, and the

members. The shire fee was the

southern part; under a sheriff appointed

by the chief Lord: the chief landowners

owed suit and service—

i.e., they attended

and were under the jurisdiction of the

shire court held monthly in the castle

enclosure, and each owed a fixed amount

of military service—especially the duty of

“castle-guard”—supplying the garrison

and keeping the castle in repair. There

are indications of the work of the shire

court in some of the castle accounts

published in the Cardiff Records,

e.g., in

1316, an official accounts for 1d., the price

of “a cord bought for the hanging of

thieves adjudged in the county court:

stipend of one man hanging those thieves

4d.” The “members” consisted of ten

lordships (several of which were in the

hands of Welsh nobles): these were much

more independent; each had its own court

(with powers of life and death), from

which an appeal lay to the Lord’s court at

Cardiff: generally they owed no definite

service to the Lord (except homage, and

sometimes a heriot at death), but on failure

of heirs the estate lapsed to the chief Lord.

At Cardiff Castle the Lord had his

chancery, like the royal chancery on a

small scale—issuing writs, recording services

and grants of privileges, and legal

decisions: practically the whole of these

records have been lost—and our knowledge

of the organization of the Lordship

is mainly derived from the royal records

at times, when owing to minority or

escheat, the Lordship was under royal

administration. The Lord of Glamorgan

owed homage, but no service to the king;

and (though this was sometimes disputed

by his tenants and the royal lawyers), no

appeal lay from his courts to the king’s

court. The machinery of government

was probably more complete and elaborate

in Glamorgan than in any other

Marcher Lordship.

Caerphilly Castle had not the political

importance of Cardiff, but far surpasses

it as a fortress. By the strength and

position of Caerphilly, one may measure

the power of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd after

the Barons’ War and before the accession

of Edward I. The Prince of Wales had

extended his sway down as far as Brecon,

and Welshmen everywhere were looking

to him as the restorer of their country’s

independence. Among them was the

Welsh Lord of Senghenydd, one of

the chief “members” of Glamorgan, and

his overlord probably saw reason to

suspect his loyalty. An alliance between

him and Llywelyn would open the lower

Taff Valley to the Welsh prince and give

him command of the hill country north of

Cardiff. It was on the lands of the lord

of Senghenydd that Gilbert de Clare, Earl

of Gloucester, built Castell Coch and Caerphilly.

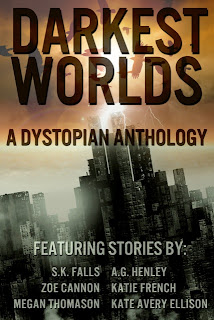

CARDIFF CASTLE. (12th Century)

CAERPHILLY CASTLE. (13th Century)

Caerphilly has been described as the

grandest specimen of its class; it represents

the high-water mark of mediæval

military architecture in this country, and

was the model of Edward I.’s great castles

in the north. It illustrates the influence

of the Crusades on Western Europe,

being an instance of the “concentric”

system of defences, of which the walls

of Constantinople afford the most magnificent

example, and which the Crusaders

adopted in many of their great fortresses

in the East.

Caerphilly Castle consists of three lines

of defense, and the way in which these

supplement each other shows that the

work in all essentials was designed as

a great whole; it did not grow up bit by

bit. There are of course many evidences

of alterations and rebuilding at later times;

the buildings in the middle ward, on the

south side, seem to be later additions; the

hall appears to have been enlarged, and

the tracery of the windows suggests the fourteenth century; the state-rooms to the

west of the hall have been much altered;

but such alterations as appear are confined

to the habitable part of the castle, and do

not affect it as a military work. It has

been suggested that the castle may have

been greatly enlarged in the latter years

of Edward II., when it played an important

part in connection with the

division of the Gloucester inheritance

and the younger Despenser’s ambitions.

There are a number of notices of the

castle in the chronicles and public records

of that time, but apparently no references

to any building operations. And the

unity of plan is evidence that the whole

dated from the same time.

The castle is built on a tongue of gravel

nearly surrounded by low, marshy land,

forming a sort of peninsula; a stream

on the south running eastwards to the

Rhymny; and two springs on the north.

By damming these waters and cutting

through the tongue of gravel an artificial

island was secured for the site of the

castle. The inner ward, or central part

of the castle, consists of a quadrangle with a large round tower at each corner:

in the center of the east and west side

are massive gate-houses defended by

portcullises; from the projecting corner

towers all the intervening wall was commanded.

The gateways communicate

with the second line of defense or middle

ward. This completely encircles the

inner ward, on a much lower level; it is

a narrow space bounded by a wall, with

low, semi-circular bastions at the corners;

it is commanded at every point from the

inner ward; the narrowness of the space

would prevent the concentration of large

bodies of assailants or the use of

battering-rams, and communication is at

several points stopped by walls or buildings

jutting out from the inner ward. The

middle ward had strong gate-houses at the

east and west ends, and was completely

surrounded by water—east and west by

a moat, north and south the moat widens

into lakes: note how on the north a

narrow ridge of gravel has been used

to ensure a water moat on that side, in

case there was not enough water to flood

the whole lake. These lakes form part of the third line of defence or outer ward,

which includes also on the west the “horn-work”

and on the east the grand front. The

horn-work is about three acres in extent,

surrounded by a wall 15 feet high, which

is of the nature of an escarpment, the

ground rising above it. It is entirely surrounded

by a moat, and connected with

the middle ward on one side and the

mainland on the other by drawbridges.

It would probably be used for grazing

purposes, and thus would be of great

value to the garrison; but so far as the

actual defences of the castle are concerned,

a lake would have been much

more effective; the nature of the ground

would however have prevented this. The

horn-work was intended to cover the only

side upon which the castle was open to

an attack from level ground, and to occupy

what would otherwise have been a dangerous

platform.

The eastern side of the outer ward—the

grand front—is a most imposing structure.

It is a wall about 250 yards long, and in

some parts 60 feet high, furnished with

buttresses and projecting towers from

which the intervening spaces are easily

commanded, culminating in the great gate-house

near the centre, and terminating at

both ends in clusters of towers which

protect the sally-ports. On the outside

is a moat spanned by a double drawbridge.

The northern part of this front,

which was probably occupied by stables,

would in dry weather be the least defensible

part of the castle; but it was

cut off from the rest by an embattled wall

running from the gate-house to the inner

moat and pierced only by one small and

portcullised gate. The southern half

was more important and stronger. It

crossed the stream at the dam, the walls

being 15 feet thick where subjected to the

pressure of the water, and the strong

group of towers at the end—on the other

side of the stream—guarded the dam on

which the safety of the castle largely

depended; the wall and towers here form

a semicircle, curving back into the edge

of the lake, so as to avoid the danger of

being outflanked.

On the inside of the grand front were

various buildings, such as the mill. This

eastern line was divided from the middle

ward by a moat 45 feet wide—a space

which is too wide to be spanned by

a single drawbridge, and as there are no

signs of the foundations of a central pier,

it seems probable that the bridge rested

on a wooden support, which could be

removed when necessary, and the assailants

plunged into the moat below.

There are a large number of interesting

details connected with both the military

functions of the castle and its domestic

economy. There were at least four exits

(not counting the two water-gates); this

would give the garrison opportunities of

harassing assailants by sallies, and would

make a much larger army necessary in

order to blockade the castle; contrast the

single narrow entrance to the Norman

keep—high up in the wall and visible to

all outside. The water-gates are worth

studying, especially the methods of protecting

the eastern water-gate—two grates

with a shoot above and between them. One

should notice, too, the “splaying” of the

outer wall, by which missiles from the top

would be projected outwards; and also the

use of the mill-stream to carry away the

refuse of the garderobe tower. And there

are many other points, to which one would

like to call attention, if time allowed.

The history of Caerphilly in the

Middle Ages need not detain us long.

It was besieged by Llywelyn in 1271,

while it was being built. Llywelyn

declared he could have taken it in three

days if he had not been persuaded to

submit the dispute to the arbitration of

the king. It is clear that the castle was

not finished; shortly after this Gilbert de

Clare obtained license from the king to

“enditch” the castle: such license was

not, as a rule, required in the Marches

(as it was in England) and was only

necessary now because the king was acting

as arbitrator. The Earl of Gloucester

kept possession. We next hear of it in

1315, when it resisted the attack of

Llywelyn Bren. It was then in the

hands of the king, pending the division

of the Gloucester inheritance among the

three co-heiresses. In 1318 Caerphilly,

with the rest of Glamorgan, was granted

to the younger Despenser, who perhaps enlarged the hall and made the other

alterations referred to above. Edward II.

was there for a few days when flying for

his life; had he trusted to Caerphilly,

instead of fleeing further through South

Wales, he might have saved his head and

his crown; at any rate, there would have

been a great siege to add to the history

of mediæval warfare. The king’s adherents

held out in Caerphilly for months,

and only surrendered when, the king

being dead, there was nothing more to

fight for, and they were allowed to go

free. Happy is the castle which has no

history. The perfection of Caerphilly as a

fortress saved it from serious attacks.

&

The Gifts Are All Free

However, If you would like to enter to win a

PDF or Kindle copy of my old-fashioned Regency Romance

A Very Merry Chase

with a personalized inscription,

please leave a comment below.

Smiles & Good Fortune,

Teresa

************************************

It

is not wealth one asks for, but just enough to preserve one’s dignity,

to work unhampered, to be generous, frank and independent. W.

Somerset Maugham (1874-1965) Of Human Bondage, 1915